“Most software companies do not die from lack of features. They die from interest payments on technical debt.”

The market punishes slow product teams. Technical debt rarely shows up on a P&L, but it shows up in growth rates, in churn, and in down-round valuations. The pattern is simple: as tech debt compounds, release cycles stretch, bug counts rise, engineers leave, and customer NRR slides. By the time the board starts asking “Why is engineering headcount up 40 percent and roadmap velocity flat?”, the company has already paid years of invisible interest.

Investors look for a clean story: capital goes in, product velocity goes up, revenue grows faster than headcount, and gross margins hold. Technical debt breaks that story. It turns each new feature into a negotiation with the past. That hits business value directly: higher CAC because the product lags competitors, lower LTV because customers do not trust stability, and weaker exit multiples because the acquirer sees a codebase that looks like a liability instead of an asset.

The trend is not clear in monthly metrics at first. Net revenue retention looks fine. Sales pushes deals over the line. Engineering still ships. Then estimates start to slip. A “two-week” feature takes six. Bugs that “cannot happen” start closing big logos. Security audits find legacy modules no one wants to own. Product leadership asks for “just one more quarter” before refactor work. The company stays in denial until burn rises, runway falls, and growth no longer hides the cost.

Technical debt by itself does not kill a software company. The combination of debt plus growth targets plus weak discipline does. The market currently rewards teams that treat technical debt as a balance sheet item with a real cost of capital. The ones that treat it as “engineering hygiene” tend to misprice it. That mispricing shows up later as layoffs, missed quarters, and distressed M&A.

What Technical Debt Really Is In Business Terms

The classic metaphor says technical debt is like financial debt: you take a shortcut now, you pay interest later. That metaphor is fine, but for a founder or CFO, it is too vague. The real business question is: “How much future cash flow do we give up for this shortcut?”

Think in three parts:

1. Principal: The size of the compromise in code, architecture, or process.

2. Interest: The extra time, risk, and cost each time you touch the affected area.

3. Interest rate: How often that area gets touched as the product grows.

A “hack” in a cold path that few features depend on has low interest. A hack in your core billing logic has a high interest rate. That is where companies get surprised. They ship a “temporary” shortcut in a central area, growth accelerates, and suddenly every feature goes through that minefield.

Expert view: “Bad code you never touch again is clutter. Bad code on a hot path is a tax on every future roadmap decision.”

From a business view, technical debt is any product or engineering decision that:

– Reduces delivery speed for future work

– Raises failure risk or incident risk

– Raises the cost to scale the user base or feature set

– Reduces exit value because acquirers see higher integration cost

The market currently prices engineering quality into valuations, especially for later stage SaaS. Buyers ask hard questions about upgrade paths, test coverage levels, modularity, and cloud cost predictability. Weak answers reduce the multiple, no matter how strong the logo sheet looks.

How Tech Debt Compounds Into A Silent Killer

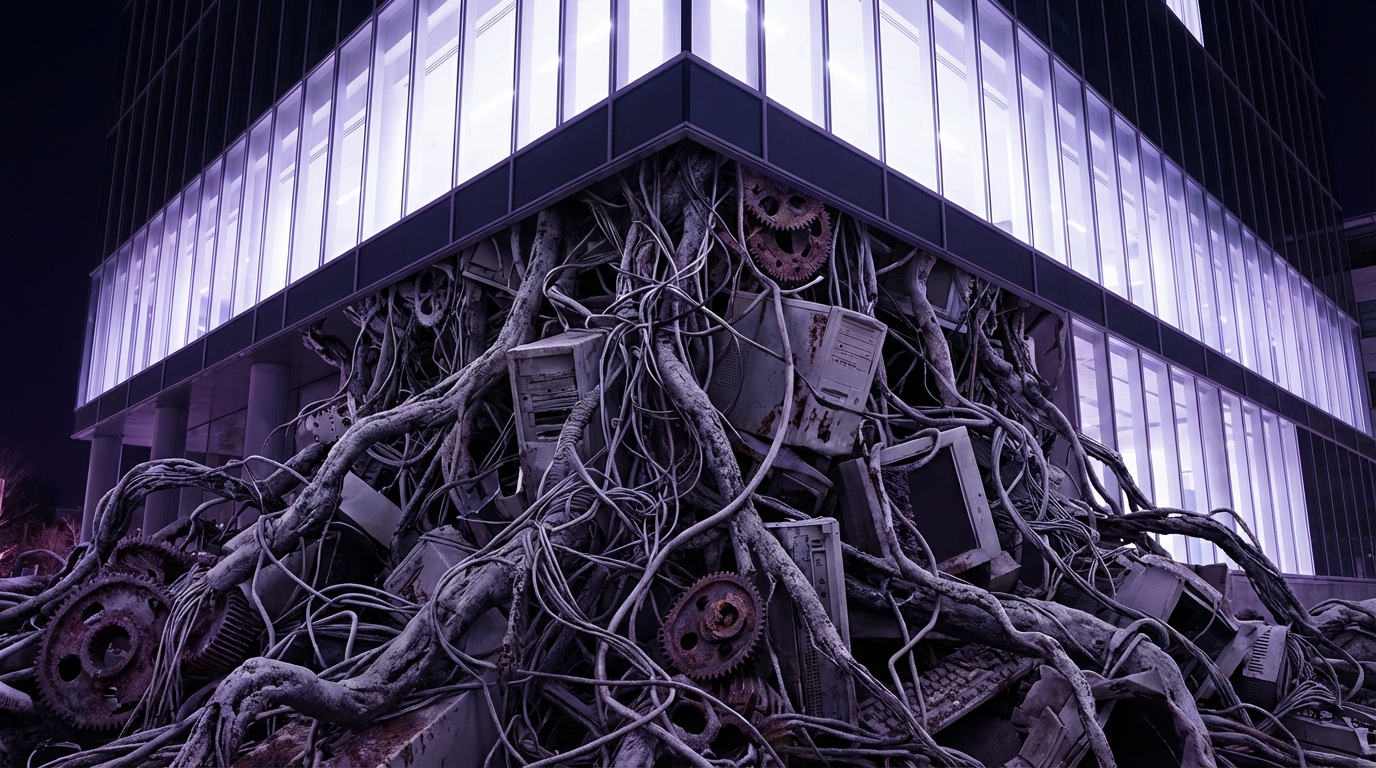

The danger is not a single shortcut. The danger is compound interest. Once tech debt reaches a certain level, the organization changes its behavior around it. That behavioral change is what kills the company.

The Compounding Loop

Here is the typical loop:

1. Product promises aggressive timelines to win deals or hit OKRs.

2. Engineering cuts corners to hit dates: fewer tests, less refactor, quick patches.

3. Bugs and outages increase. New features take longer than estimates.

4. Trust between product and engineering erodes. Leadership pushes harder.

5. Team morale drops. Senior engineers either disengage or leave.

6. New hires struggle to understand the codebase and repeat old mistakes.

7. Technical debt grows faster than headcount or revenue.

Data point: A 2019 Stripe survey reported that developers spend about 33 percent of their time dealing with technical debt and bad code. That is one engineer day out of every three, across the entire org, not spent on net-new value.

From a P&L standpoint, that means if you have a $5 million yearly engineering budget, roughly $1.5 million may go to cleaning up after previous shortcuts. For many growth companies, that number is higher because architectures are changing more rapidly.

The ROI Distortion

Investors look for a strong ratio between new R&D spend and new ARR. Technical debt quietly distorts that ratio.

– Early stage: $1 of engineering spend can create $5 to $10 of ARR growth, because the codebase is young and flexible.

– Mid stage with rising tech debt: that same $1 might only create $2 to $3 of ARR, because much of the capacity goes into maintenance and rework.

– Late stage with heavy tech debt: $1 might create less than $1 of new ARR, because the team fights fires instead of shipping meaningful improvements.

When leadership sees the ratio fall, the typical reaction is to “add more engineers” instead of asking “Why is every feature taking longer?” That adds payroll cost but not velocity, which hits runway and valuation.

How To See Tech Debt In Your Metrics

Technical debt does not have a line item, but it leaves fingerprints in product and business metrics.

Operational Signals

Engineering leaders tend to feel tech debt before executives see it. Still, executives can watch for:

– Growing gap between estimated and actual delivery timelines

– Rising number of regressions after releases

– More emergency hotfixes in production

– Increasing “bus factor” areas where only one engineer can safely make changes

– Declining engineer NPS or engagement survey scores tied to tooling and codebase quality

Expert view: “When senior engineers spend more time warning about ‘unknown side effects’ than discussing product trade-offs, you are not shipping a roadmap, you are rolling dice.”

Business Signals

Technical debt also shows up in:

– Slower feature response to market needs

– More customer complaints about reliability or bugs

– Harder security audits and longer sales cycles for enterprise deals

– Lower customer expansion because teams fear turning on more modules

None of these alone proves a tech debt problem. Combined, they tell a story.

The Real Cost Of Tech Debt Across Company Stages

Technical debt is not always bad. The cost and benefit change with stage. The market often rewards early risk-taking but punishes late-stage fragility. The trick is knowing when the trade flips.

Early Stage: Pre-Seed To Series A

At this stage, the primary risk is building the wrong thing. Shipping speed matters more than code elegance.

Business logic:

– Time to product-market fit has more impact on valuation than code quality.

– A lot of early code will get replaced.

– Burn rate is sensitive, so heavy architecture work with no near-term revenue signal is hard to defend.

Still, there are traps:

– Building a monolith with no clear boundaries around core domains

– Hard-coding pricing, permissions, or workflows that clients will want to change

– Ignoring basic security practices to save time

The hidden business risk is that first big logo. Enterprise pilots often demand custom work. If that work lands on a weak foundation, you lock in unhealthy patterns that will slow every future deal.

Mid Stage: Series B To Series D

Here the risk shifts. The product has found a market. Now the constraint is execution. This is where technical debt often turns from a trade to a drag.

Investors want:

– Predictable release cycles

– Clear roadmap tied to revenue opportunities

– Evidence that unit economics improve with scale

Technical debt cuts across each:

– Predictability: estimates slip more as dependencies grow.

– Roadmap: product managers start “negotiating with the codebase” instead of with customers.

– Unit economics: cloud costs rise faster than revenue because scaling is inefficient, and maintenance headcount grows.

This is usually the stage where companies should spend serious time and money to address tech debt. Many do not. They see refactor work as “non-revenue producing”, even while they approve vague “platform” projects because the label sounds more strategic.

Late Stage and Pre-Exit

In a pre-IPO or pre-acquisition context, technical debt directly affects valuation. Buyers and public investors ask detailed questions about:

– Release reliability history

– Security posture and incident track record

– Codebase modularity and integration effort

– Cloud cost trends as revenue scales

If tech debt has forced patchwork solutions, the story becomes harder to sell. Acquirers discount heavily when they see long-term integration work.

Data point: In tech M&A, acquirers often set aside 10 to 20 percent of the purchase price as post-close “remediation” budget when they suspect heavy technical debt. That budget effectively lowers the real valuation.

Types Of Technical Debt That Matter Most For Business

Not all tech debt has the same impact on business value. Some categories hit revenue harder than others.

1. Architecture Debt

Architecture debt shows up when the original structure of the system no longer fits the scale or feature set. Signs:

– Every minor change touches many areas

– No clear ownership boundaries

– Hard to scale specific hot components without scaling the whole stack

Business impact:

– Slower time to market for complex features

– Higher outage risk when usage spikes

– Difficulty serving larger customers with more complex needs

2. Data Debt

Data debt includes weak schemas, lack of clear ownership of data models, and ad hoc integrations.

Business impact:

– Reporting that does not match customer reality, which breaks trust

– Slower adoption of analytics and AI features because data is messy

– Compliance and privacy risk during audits

3. Process And Tooling Debt

This is the gap between what the team should have in place to ship safely and what it actually has. Missing tests, manual release processes, weak monitoring.

Business impact:

– More incidents and longer incident resolution

– Slower onboarding for new engineers

– Higher error rate in production, which hurts NPS and expansion

4. Security Debt

Security debt includes outdated libraries, weak access control, and incomplete logging.

Business impact:

– Direct breach risk with heavy financial and reputational impact

– Slower enterprise sales as security reviews surface issues

– Higher cyber insurance premiums

How Different Pricing Models Hide Or Reveal Tech Debt

The way a software company charges clients changes how tech debt hits the P&L.

Tech Debt Under Different Revenue Models

| Pricing Model | How Tech Debt Shows Up | Business Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Seat-based SaaS | Slow feature delivery reduces expansion per customer | Lower NRR, slower up-sell, higher churn to faster rivals |

| Usage-based | Performance issues or outages reduce usage volume | Revenue volatility and weak growth in heavy-usage tiers |

| Implementation + license (enterprise) | High customization cost because of brittle core | Fewer deals closed, cost overruns in projects, margin erosion |

| Freemium | Bugs and rough edges in free tier limit upgrade funnel | High acquisition but low conversion, wasted marketing spend |

| Marketplace / platform fee | API instability and integration issues slow partner growth | Fewer active partners, weaker network effects |

Investors look for consistency between revenue model and engineering reality. For example, a usage-based company with performance-related tech debt faces a direct revenue cap. A seat-based SaaS can hide that for longer, but churn and lower expansion will show up eventually.

Valuing Tech Debt Like A Balance Sheet Item

Most product roadmaps treat tech debt work as low-priority maintenance. That framing underestimates its business impact. A better lens is financial.

Simple Way To Approximate Tech Debt Cost

You can build a rough model with three numbers:

1. Engineering cost per engineer per year

2. Percentage of time spent wrestling with tech debt

3. Extra revenue per year you could likely ship with that time back

Example:

– 25 engineers, average fully loaded cost: $200k per year

– Engineering budget: $5 million

– Survey and tracking show ~35 percent of time spent on rework, regressions, and dealing with fragile code

Direct cost of tech debt per year:

– 0.35 * $5 million = $1.75 million

If the company typically generates $200k of new ARR per engineer-year of net-new work, then the lost capacity implies:

– 25 engineers * 0.35 = 8.75 engineer-years lost

– 8.75 * $200k = $1.75 million potential ARR growth delayed or lost each year

So tech debt here costs around $3.5 million yearly, half in direct payroll, half in delayed growth. If the revenue multiple is 6x, that is $10.5 million of enterprise value drag each year this state continues.

Investor view: “A company with strong growth and high debt still gets funded. A company with slowing growth and high debt gets repriced.”

Comparing Tech Debt Strategies

Different companies choose different levels of tolerance for tech debt. Here is a simplified comparison.

| Strategy | Short-Term Benefit | Long-Term Effect On Value |

|---|---|---|

| “Ship at any cost” | Very fast early feature growth, easy to impress early adopters | Sharp slowdown at scale, heavy refactor cost before exit |

| “Quality gatekeepers” | Slower early velocity, fewer bugs and incidents | More predictable velocity at scale, easier due diligence |

| “Scheduled cleanup” | Balanced roadmap with dedicated refactor capacity | Stable long-term development cost and lower risk profile |

Founders often fear that any investment in refactor work will hurt growth. The market history suggests the opposite: predictable velocity and reliability produce higher quality revenue, which investors value.

How Leadership Accidentally Fuels Tech Debt

Technical debt is not only an engineering problem. It is often created by management patterns.

Incentive Misalignment

Common patterns:

– Sales rewarded only on bookings, pushing custom commitments that bypass product strategy.

– Product rewarded on feature count or release dates, not on stability or predictability.

– Engineering rewarded for heroics during incidents, not for preventing incidents.

These incentives push teams toward short-term wins that add long-term cost.

Roadmap Theater

Many roadmaps treat capacity as fixed and tech debt as optional. Quarterly planning meetings fill every slot with new features to tell a strong growth story to the board. There is no reserved capacity for:

– Refactors in core modules

– Migration away from deprecated infrastructure

– Improving test coverage and automation

In practice, those things still happen, but as firefighting during crunches. The result is unreliable delivery and higher stress.

Underestimating Context Cost

When codebases become messy, engineers spend more time building context before making changes. This context cost rarely shows in planning. Managers see “one feature per sprint” slowing to “half a feature per sprint” and assume effort is low, not that complexity is high.

Practical Ways To Bring Tech Debt Into Business Conversations

To stop tech debt from becoming a silent killer, leadership needs a shared language. That language must connect directly to revenue, risk, and valuation.

Translate Debt Into Revenue And Risk

Instead of “We need to refactor the billing service”, frame it as:

– “Current billing code makes any new pricing model a 3-month project. With this refactor, we can ship new models in 3 weeks. Finance expects at least one new pricing experiment per quarter to hit growth targets.”

Or:

– “Our lack of proper audit logging will fail the next enterprise security review. Fixing this now means we can close higher-ACV deals without custom security exceptions.”

When tech debt is tied directly to money left on the table or deals at risk, it becomes easier to prioritize.

Set Explicit Budget For Tech Debt Work

Many strong product organizations reserve a consistent share of engineering capacity for non-feature work. For example:

– 60 percent of capacity: roadmap features tied to growth or retention

– 20 percent: tech debt reduction in high-impact areas

– 10 percent: reliability and performance

– 10 percent: experimentation and R&D

The actual numbers vary, but the key is that tech debt work has a stable allocation. That stability makes planning easier and prevents spikes of urgent but unplanned remediation.

Use Lightweight Debt Accounting

You do not need a complex system. A simple approach:

– Engineers tag tickets that exist only because of past shortcuts.

– Teams track “debt-related hours” each sprint.

– Product and engineering review monthly where that time went and what it signals.

Over time, this creates data on:

– Which parts of the system carry the highest interest

– How much capacity tech debt absorbs

– Whether things are trending better or worse

This is not perfect accounting, but it anchors strategic conversations.

Tech Debt Benchmarks Investors Quietly Use

Investors and acquirers rarely share exact checklists, but some patterns are common in technical diligence.

Architecture And Process Checks

Questions often include:

– How long does it typically take to ship a medium-sized feature from spec to production?

– How often do releases get rolled back?

– What percentage of code has automated test coverage, and in which layers?

– How easy is it to run the full system locally for development?

Short, clear answers give confidence. Long, hedged answers raise flags.

Growth Metrics That Hint At Tech Debt

Certain growth metrics can imply deeper technical issues:

| Signal | What Investors May Infer |

|---|---|

| Slowing expansion revenue from existing customers | Difficulty shipping requested features or modules |

| High churn on larger customers vs small ones | Platform struggles at higher scale or complexity |

| Rising gross margin pressure from cloud spend | Inefficient architecture, often linked to tech debt |

| Frequent roadmap slips over last 4 to 6 quarters | Underestimated complexity and hidden dependencies |

Investor comment: “We do not need perfect code. We need a team that understands its own trade-offs and has a plan to manage the debt load.”

Strategy: When To Take On Tech Debt And When To Pay It Down

Technical debt is not always bad. Used with care, it can support growth. The question is timing.

Reasonable Moments To Take Tech Debt

Tech debt makes some sense when:

– Validating a new product direction where the main risk is user demand, not security or compliance.

– Building a one-off feature for a high-value design partner, with a clear plan to either retire or rebuild it if it proves valuable.

– Supporting a time-critical external event, like a regulatory deadline or industry migration.

The rule of thumb: take debt where the upside is clear and the future clean-up path is known and realistic.

Clear Signs It Is Time To Pay Down

Refactor and remediation work should become top-3 priorities when:

– More than 30 to 40 percent of engineering time goes to rework and incident response.

– Key features require edits across many unrelated modules.

– Engineering hiring is slowing or quality of hires is dropping because senior people avoid the codebase.

– Security posture starts blocking sales opportunities or compliance reviews.

At that point, ignoring tech debt is not conserving capacity. It is burning it.

Case Pattern: How Tech Debt Kills A Promising SaaS Company

Consider a fictional B2B SaaS startup, but one that matches many real stories.

– Series A: Small team builds a monolith. The product finds fit. Customers love the core functionality. The team hardcodes a lot of stuff to move faster.

– Series B: To win larger deals, sales promises custom workflows and complex permissions. Engineering builds them by copying and tweaking code, not by developing a real permissions model.

– Year 3: The client base grows. Every big customer uses a slightly different version of the same workflows. Bug fixes for one break another.

– Year 4: Enterprise prospects ask for audit logs, SSO variants, custom reporting, and region-specific data control. The current architecture resists all of that.

– Reality: Roadmap cycles blow up. What looked like “two months of work” on a high-ACV feature consistently takes four. Sales gets frustrated. Churn ticks up as outages hit use cases the team barely understands.

The founders react by hiring more engineers. Burn rises. The board questions why growth has slowed while cost has risen. A major refactor is proposed, but that requires slowing new feature delivery, which leadership fears will hurt sales. So the company stays in a gray zone: half-refactors, half-promises.

By the time an acquirer looks, the product is successful but fragile. The buyer sees multi-year integration effort and heavy ongoing rework cost. They offer a lower price, structured with earn-outs. The founding team accepts, but the outcome is a fraction of what the early growth curve suggested.

This story is not about bad engineers. It is about a business that treated technical debt as an internal annoyance instead of as a real financial liability.

Building A Culture That Manages Tech Debt Proactively

Winning companies treat technical debt management as part of product strategy, not as janitorial work.

Shared Vocabulary Between Product, Engineering, And Finance

Strong teams agree on:

– What counts as high-interest tech debt

– How to decide when to fix vs when to defer

– How refactor work ladders up to revenue, margin, or risk reduction

Example language:

– “This refactor reduces our time to ship new integrations by half. That lets sales close more partner deals this year.”

– “Improving our monitoring stack will cut average incident downtime by 40 percent, which protects SLAs and reduces churn on top-tier plans.”

When finance hears clear cause-and-effect stories, they are more likely to back tech debt projects.

Engineering Metrics That Matter To The Business

Rather than track dozens of technical stats, focus on a tight set that correlate with business outcomes:

– Lead time: time from code commit to running in production.

– Change failure rate: percent of releases that cause incidents.

– Mean time to recovery: how fast the team fixes incidents.

– Time spent on rework versus new feature work.

Over a long enough window, improvements in these tend to support:

– Higher release frequency

– Lower churn and better NPS

– More predictable delivery for sales commitments

That predictability is valuable capital in itself.

Talent Retention As A Tech Debt Indicator

Senior engineers want to work on meaningful business problems, not only on perpetual cleanup. If your company has a pattern of senior people leaving after 12 to 18 months with comments about “tech stack” or “process”, that is an early signal that tech debt is shaping the culture.

Replacing those people is expensive. Losing their context around past trade-offs raises the interest rate on existing debt. Once too much context is gone, even simple refactors become risky.

Why Tech Debt Is A Valuation Lever, Not Just A Cost Center

Tech debt is quiet. That is why it is dangerous. But handled properly, it is also a lever.

– Companies with sound debt management ship faster with fewer surprises.

– Their sales teams can promise features with confidence.

– Their gross margins scale in a more predictable way.

– Their exit conversations focus on market opportunity, not on remediation risk.

The market currently rewards those patterns with higher revenue multiples and smoother funding roads. Technical debt sits in the middle of that story, not on the edge.

When founders and executives start talking about tech debt in terms of interest, runway, and enterprise value, they give themselves a better chance to avoid the silent killer pattern and instead treat each trade-off like what it really is: a financing decision about the future of the company.